I used to be a regular at the pet store on the second floor of my local mall, down by Sears. Whenever I had to go with my mom to run errands, at the end of our quest, I would drag her to the pet shop. I gaped at the squirmy puppies – all cartilage – and kittens no more than eyes and fluff, along with the usual sickly goldfish and colorful, preachy birds. What got me though was that they had tortoises. In a hexagon plexiglass-walled pen in the middle of the store, filled with sawdust chips and a miniature wooden house, a dozen desert tortoises casually plodded, frequently pushing into each other, like bumper cars toward the end of the ride when the mechanisms wind down. Their earthy brown-and-gold shells made them seem like boulders that had come to life, rolling about at their own will. I admired the methodical and slow yet determined pace that they kept, much like senior citizens who walked laps between Lord & Taylor and the food court.

I used to be a regular at the pet store on the second floor of my local mall, down by Sears. Whenever I had to go with my mom to run errands, at the end of our quest, I would drag her to the pet shop. I gaped at the squirmy puppies – all cartilage – and kittens no more than eyes and fluff, along with the usual sickly goldfish and colorful, preachy birds. What got me though was that they had tortoises. In a hexagon plexiglass-walled pen in the middle of the store, filled with sawdust chips and a miniature wooden house, a dozen desert tortoises casually plodded, frequently pushing into each other, like bumper cars toward the end of the ride when the mechanisms wind down. Their earthy brown-and-gold shells made them seem like boulders that had come to life, rolling about at their own will. I admired the methodical and slow yet determined pace that they kept, much like senior citizens who walked laps between Lord & Taylor and the food court.

After months of convincing, bartering, and saving up my allowance, I assembled the 60 dollars – a truly extraordinary sum for a sixth grader – to purchase one of these tortoises. He came home in a cardboard carrier, bumping and thumping the whole car ride. At home, in his glass aquarium, I would sit so close to the heat lamp that it threatened to burn my skin, as I stared with fascination at his beaky face, beady black eyes, and wrinkled mouth and neck. He reminded me of a late-in-life Clint Eastwood. He clunked all over his enclosure, brazen, bold and rarely tucked into his hinged, brown and yellow shell. Even when sleeping, often his arms and legs would sprawl out. This was a turtle without fear.

At this time, I was obsessed with a book called 1,001 Names for a Baby. I was fascinated by the full page of nicknames for Elizabeth (Liz and Beth, sure, but Betty or Becky?), and used this brick of a paperback to find unusual names for all of my stuffed animals and pets. I started with the As in the boy-name section to find one appropriate for my new tortoise. I didn’t get very far though. As soon as I saw that Aristotle was the name of some ancient philosopher, and as no one seemed more stoic, thoughtful, or philosophic than this desert tortoise, it was over. I threw in Aaron for a middle name for a nice alliteration, and he was christened.

Perhaps Plato would have been a better-suited name for my tortoise, because Aristotle was not content confined to the cave. He wanted to leave and experience the light of the world for himself. Staying true to his disgruntled disposition of an old man, Aristotle wasn’t satisfied by his surroundings. Every day he spent hours and hours every day, clawing at one corner of the aquarium. His head pressed against the seam of the two perpendicular glass panels, his front legs and sides of his shell smashing into the sides. He seemed to think that if he slammed hard enough, one day that glass corner would give out and he would be free. He also might not have been too bright, but I refused to think less of my new tortoise. He was probably deranged.

As the New England slush and mud subsided, and the outdoors began to resemble Aristotle’s native desert climate, I started to take him out for walks. Our house in the Massachusetts suburbs had a fenced-in backyard, and I would spend hours on the porch reading Roald Dahl (clearly Esio-Trot – his short book about a man in love with a woman in love with her pet tortoise – was my favorite), letting Aristotle roam free, getting up every twenty minutes or so when he got a little too far away for my liking. I would pick him up and bring him back to the stairs where he would start on his journey again: jetting through the grass in spurts, pausing for a rest, slowly pushing his way through dead leaves and stems, determined. It wasn’t hard to keep him in line though: as much ground as a tortoise can cover, a human is usually faster.

In the summer, my family rented a house on a small island in Long Island Sound, so we loaded Aristotle’s aquarium into the back of my mom’s station wagon and endure two hours of clunking. My mom seemed on the verge of a breakdown by the time we arrived at the ferry dock. Once on the island, though, Aristotle was in tortoise heaven. No fence at our house that summer, but a huge grassy sprawl that had never been manicured. The lawn was a dry, yellowy green and brown, with patches of dusty, sandy dirt between half-exposed rocks. With all of that, plus the intense July sunshine, Aristotle must have felt that he was back in his desert home. I would spend hours reading on the porch – this time Sharon Creech or Lois Lowry or Gary Paulsen – continuing my routine of getting up every twenty minutes or so and bringing him back to the starting point. He was like a mechanical toy in trajectory and pace. He certainly was not fast, but he could get away from you.

Besides reading books on the porch, reading books on the beach, and sitting outside with Aristotle, there was not much to do on the island, so I started to hang around the tiny local library volunteering to shelve books and helping older women check their email. I was never paid, but somehow I never had any late fees and won first place in the July Creative Writing Contest.

It was on one of these days, when I was at the library, that my dad got frustrated with Aristotle’s relentless crashing into the corner of the glass aquarium. My dad ran his own company, advising investors, and, that summer, he could work remotely from the island, frequently conducting conference calls in no shirt and a bathing suit still damp from a morning swim at the beach. On that particular day, my mom was off in the town center with a few family friends who were visiting us, and it was unclear when I would be back from the library. So, my dad took Aristotle outside with The New York Times, and sat and read and had another cup of coffee. Aristotle strolled through the dried grass, making great strides until my dad would get up and bring him back. But then the phone rang inside. My dad got up to answer what turned out to be an important call, and talking business and meetings, he became distracted, and forty minutes later when he came back outside, Aristotle was nowhere to be found.

When I came back from the library, I knew instinctively that something was wrong, similar to returning home and seeing an ambulance or a police car, red-and-blues flashing, parked outside. My mom, dad, and our family friends were circling the house, all three kids from next door, their parents, and the entire family from across the street were all outside, some on hands and knees. Two boys were crawling under our porch when I figured out what happened.

“Where. Is. Aristotle.”

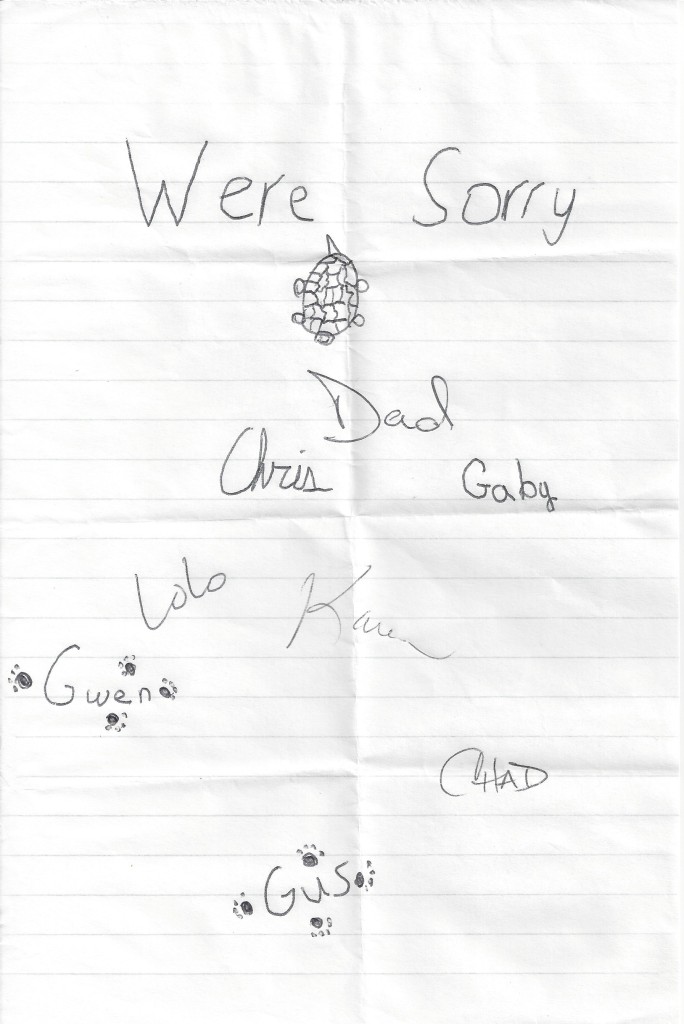

I didn’t even let my father explain before I screamed. I ran to my room, shrieking, hyperventilating, letting all of my thirteen-year-old hormonal emotions flow free and violent. My skin was red and dry from the salty water streaming down my face. I had trouble breathing evenly. I refused to speak to my dad when he came upstairs to apologize. The tantrum lasted through dinner, through a homemade card made by the daughter of our family friends (Were [sic] sorry with a drawing of a turtle, signed by my parents, my brother, our family friends, and both of our dogs), through several days, when it became clear that Aristotle was gone and not coming back:

My grandmother called me on the phone to comfort me:

“Oh, Elizabethy. Animals shouldn’t be kept in cages. Think of how happy Aristotle is now. He’s probably swimming with his other turtle friends in the ocean as we speak!”

“Nunni,” I said darkly, my voice thick with teenage anger and angst, “he’s a desert tortoise. If he’s in the ocean, he’s dead.”

I used Aristotle’s loss as leverage for years: “Oh, I can’t stay out past 11?” I would say as a teenager, “You know who’s always out past 11 now? Aristotle.” I especially liked to guilt trip my dad. Almost a decade and a half later, I emailed him a news story. A family in Brazil lost track of their red-footed tortoise named Manuela in 1982. They searched to no avail, and eventually gave up, assuming that Manuela had run off after some maintenance workers had left the door to the house open. Thirty years later, cleaning out the house after the father of the family had died, the grown children opened a box they found in a locked storage closet. Inside the box, they discovered an old record player and a red-footed tortoise.

Manuela had survived three decades on termites alone.

There’s hope yet.

E.B. Bartels is from Massachusetts and writes nonfiction. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, Ploughshares, Fiction Advocate, and the anthology The Places We've Been: Field Reports from Travelers Under 35 among others. See her website at www.ebbartels.com, tweets at @eb_bartels, and read her haikus about strangers’ dogs at ebbartels.wordpress.com.