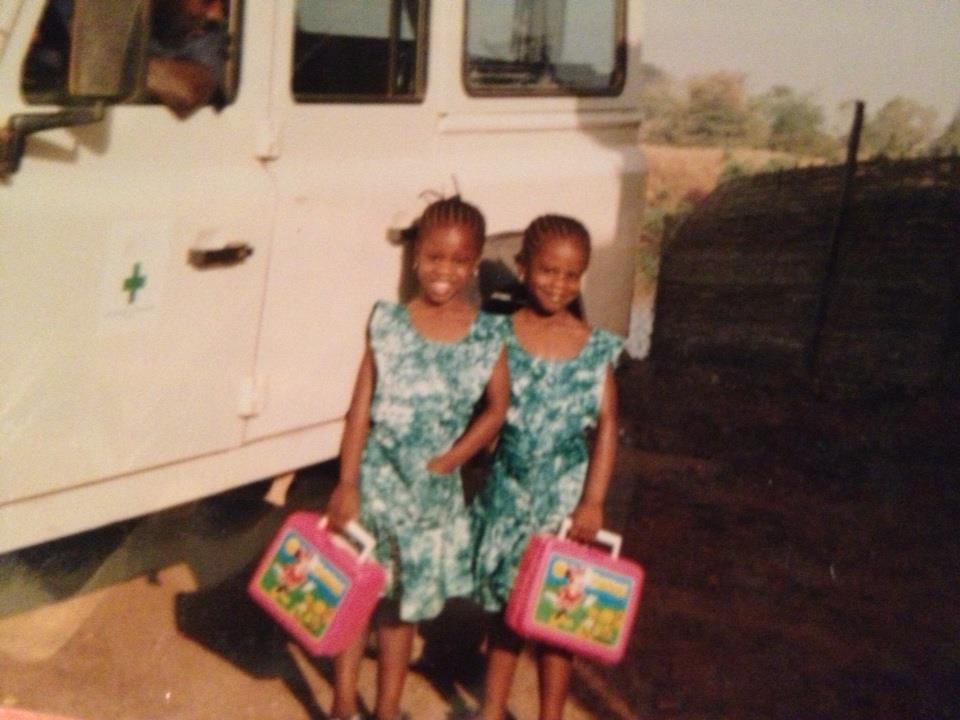

It’s 1998 in Finneytown, Ohio. I’m seven years old and treading water in the YMCA pool. So is my twin sister. The swim instructor, a blond, nondescript woman wearing one of those ugly block color bathing suits is standing at the edge of the pool. A few weeks later, she will save my life when I jump into the deep end, trying to impress my dad with my newly acquired swimming acumen. My dad, back from a long trip to the Gambia, will think I’m waving to him. But that’s not for a few weeks. Right now the swimming instructor is perplexed. It is Friday, October 31. Around 6pm in the evening. And we are the only kids in the pool.

“Aren’t you going to go trick-or-treating?” she asks us.

In retrospect, maybe she wasn’t concerned so much with the social repercussions of our not trick-or-treating as she was irritated that she still had to teach that Friday night.

“No,” we both say.

Of all the American rituals to explain to a foreigner, Halloween is the hardest. It just sounds so dangerous. Dressing up in costumes that make you indistinguishable from one another, knocking on the doors of strangers (white people most likely) and begging for candy. Maybe your neighbors aren’t supposed to be strangers, but when you’re immigrants and your base knowledge of America is supplied by CNN and Jamie Lee Curtis movies, it makes sense to be cautious. I mean, when you really think about, it wasn’t a big surprise my parents said heck no to Halloween.

We had moved to America a few months earlier and my sister and I were just trying to keep up. The Spice Girls were huge, “That was the bomb” was the highest form of praise and my classroom crush Roger had told me in that casually devastating way of second graders that my breath stank. I still hadn’t recovered.

Kids would ask us where we were from and we told them we were Nigerian but lived in the Gambia, this tiny, tiny place off the coast of the Atlantic, the size of your fingernail on a map, where we lived in a nice large house with a maid and a driver and a gardener and no, there were no lions only crocodiles in this special place called Kachikally. You could stroke their backs and they looked like statues because they were so still and white. They were supposed to make you fertile.

That Friday, we went home and took out our cornrows. We watched a Halloween-themed edition of Kids Say the Darndest Things. Neighbors rang the doorbell. We had no candy.

The seed of discontent was born.

Over the years, when asked why I didn’t trick-or-treat or play with ouija boards or read tarot cards or follow my horoscope, or why I hated the whole fortune-telling plotline in the Harry Potter books (books I read clandestinely, intrigued enough by the attention to detail in this alternate universe to ignore the fact that they were all witches and wizards), I would struggle to explain.

In the West, perhaps I would begin, a little pompously, people don’t think witchcraft is real. But in Nigeria, some people consult witch doctors. Pastors drive out demons. In 2001, the torso of a young African boy was found floating in the River Thames. Police never confirmed the identity of the boy, but it was believed to be the result of a ritual killing.

Our film industry, Nollywood, thrives off the evil machinations of jealous wives who slip their husbands herbal medicines to render them infertile. My grandmother, who lives in Kaduna, talks casually about the witch they drove out of their church. Penis theft is a thing. People join cults, get possessed. To my very conservative Christian parents, any celebration of the dark arts, coupled with the whole begging white people for candy thing, naturally made Halloween festivities of any kind strictly verboten.

So my parents oscillated between indifference and active hostility towards the holiday depending on where we were living at the time. We moved to Rhode Island a few years later and we had a little brother now and since he was a boy and the youngest, when our friendly next door neighbor asked if he wanted to go trick-or-treating with them— my mother surprisingly said yes. (I suspect it had something to do with the fact that our neighbor’s new husband was Moroccan. He was at least from the continent.) I decided to come along even though I didn’t have a costume. Our neighbor’s son gave me a red clown wig. My brother wore a firefighter’s outfit he had handy from a school play and we walked around the neighborhood in the semi-darkness. I acquired an ongoing affection for Milk Duds. Otherwise, nbd, I thought.

When we moved to Pittsburgh, we went to a large church where there was this functioning ecosystem of Christian alternatives to the secular world—a new currency called Bible bucks and a gift store to buy fully-illustrated children’s Bibles, and hip Christian music albums. Instead of trick-or-treating on Halloween, kids could go to a harvest celebration. They could drink apple cider (hot apple juice) and frolic in the leaves and whatnot.

When my brother demanded a costume one year, my mother bought him a Bible Man costume from the family Christian store. The outfit was inspired by a famous passage in Ephesians where Christians are called to wear the breastplate of righteousness and carry the shield of faith. My brother didn’t care too much because he had a sword and a mask. He might as well have been African Thor.

As for me, I was lukewarm on Halloween too. It depended on how intense the peer pressure was that year. In high school and middle school, I’d wrap a gele on my head (stiff, brightly colored fabric worn on Yoruba women’s heads: the scourge of many a short person at any college graduation ceremony). “You look like the Chiquita lady,” the white kids would say. They loved it.

Nowadays, I have an arsenal of true statements to fling at the interlocutor who asks why I am not in costume. “Because Halloween is just an excuse for people to be racist,” I can say, or “it’s just an excuse for people to get uproariously drunk,” or “it’s just an excuse for grown people to act like children” (shout-out to A. O. Scott). It’s not like I haven’t toyed with the idea of me and sixteen of my closest friends dressing up as every Beyoncé from Beyoncé. It’s not like I haven’t contemplated dressing up as a slutty baby wearing a baggy onesie and carrying a phallic rattle.

But it doesn’t seem to be worth the effort, quite frankly. I still like Milk Duds, though.