Previous Birds of the Month can be found here.

It is dangerous to slam a portion of your body into a hard surface 15 times a second, with a force 1,000 times that of gravity. You or I could not do it. Yet acorn woodpeckers, like the 200 or so other species in the woodpecker family, are so extraordinarily designed that for them it is as relaxing a pastime as idling in a park. Here is one about to start hammering:

Male acorn woodpecker

A woodpecker’s beak is extremely strong, and built so it absorbs the impact of the hammering rather than transferring it to the bird’s organs or muscles. Its brain is small relative to the size of its body, and positioned so that it has maximum contact with (and therefore is maximally protected by) its unusually thick skull. Woodpeckers also have a thick third eyelid, which closes a fraction of a second before each stroke of the bill, in order to protect the eyes from the splinters that fly from the tree as the bird drills away.

Large white-billed woodpecker, demonstrating its strong beak

The woodpecker is so spectacularly fit for purpose that it is often used by creationists as proof of the existence of God. Ted Hughes displayed a poor grasp of woodpecker biology when he wrote

Pity the poor dead oak that cries

In terrors and in pains

But pity more

Woodpecker’s eyes

And bouncing rubber brains.

In some ways, the acorn woodpecker is a rather average example of the woodpecker family. It is average size and weight: about 8 inches and 3oz. Its plumage is on the minimalist end of the woodpecker scale: black and white with a striking red cap. (Other species throw brown and green into the mix.) You can distinguish male from female by looking at the cap: the male’s cap starts far closer to the beak, while the female has a black band between beak and cap. It lives in the woods and coastal areas of California and southern United States, through Central America and down to Colombia. Its eyes are spookily pale.

Female acorn woodpecker

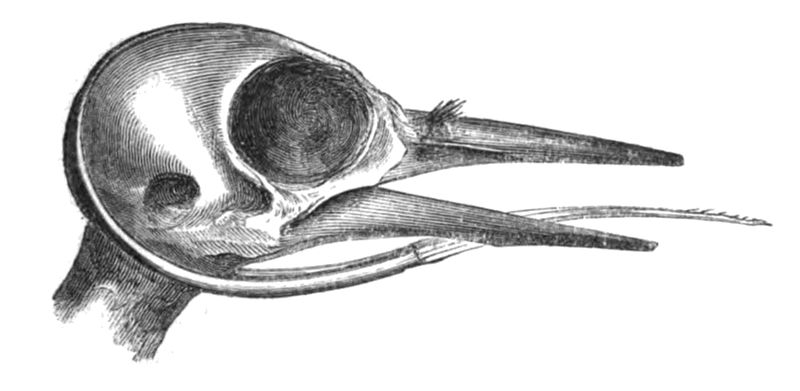

Woodpeckers drill and drum for a number of reasons – to attract a mate, to establish territory – but mostly to locate insects that live inside the bark of trees. Once the woodpecker has drilled a hole in a tree, it pokes in its long, sticky, bristly tongue, wraps it round the ant or grub or mealworm and pulls it out to eat. In this moment of feeding, it is convenient for the woodpecker to have a long tongue. The rest of the time, however, it is not so convenient, and the bird retracts the tongue so it is wrapped around the skull and drawn into the nostril.

Woodpecker skull. That long thing curving around the outside is the tongue.

Acorn woodpeckers eat a fair number of ants, but their primary food source is acorns. It is this that makes the species exceptional among woodpeckers. Acorns are located on the outside rather than the inside of oak trees. Acorn woodpeckers therefore drill into trees not in order to find acorns, but in order to make holes in which they can store acorns for later use, and especially during the winter. Here is a tree which has been attacked by acorn woodpeckers:

You can see that some of the holes have been filled with acorns. Such trees are called ‘granaries’ and may contain more than 50,000 holes. The woodpecker’s main concern is to find a hole that fits the acorn exactly.

As the acorn dries out, it decreases in size, and the woodpecker moves it to a smaller hole. The birds spend an awful lot of time tending to their granaries in this way, transferring acorns from hole to hole as if engaged in some complicated game of solitaire.

Multiple acorn woodpeckers work together to maintain a single granary, which may be located in a man-made structure – a fence or a wooden building – as well as in a tree trunk. And whereas most woodpecker species are monogamous, acorn woodpeckers take a communal approach to family life. In the bird world, this is called cooperative breeding. Acorn woodpeckers live in groups of up to seven breeding males and three breeding females, plus as many as ten non-breeding helpers. Helpers are young birds who stick around to help their parents raise future broods; only about five per cent of bird species operate in this way.

Adult bird feeding younger one inside tree

Sometimes a single brood, laid by one female, will contain eggs that have different fathers. The similarly-aged half-siblings will be raised together by a combination of biological parents, adoptive parents, older half-siblings and adoptive siblings, until they are old enough to work in the family acorn business or go off and start a granary of their own. In short, acorn woodpeckers are some kind of super-species, evolved (pace creationists) to manage their physical and familial activity efficiently and harmoniously.

When animator Walter Lantz was on honeymoon in California in 1940, he heard an acorn woodpecker pecking and calling as it stashed acorns in the roof of his cabin. Lantz’s new wife suggested that he create a cartoon based on the bird; the result is Woody Woodpecker.

You may be thinking that Woody does not look much like an acorn woodpecker. If anything, he is closer to the pileated:

Woody also does not resemble the acorn woodpecker very much in sound. Inspiration works in mysterious ways. Here is the pleasant-ish call of an acorn woodpecker:

Here is the less pleasant laugh of Woody Woodpecker, repeated across a whole hour. I lasted 28 seconds. You?

Hannah Rosefield likes writing about books and birds. She lives in London and tweets.