This post was brought to you by a reader.

This post was brought to you by a reader.

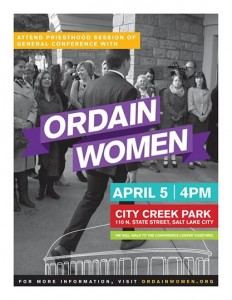

Editor’s Note: This story was published while about 500 Ordain Women participants were preparing to enter Temple Square, during the Mormon Church’s General Conference on April 5. A few weeks earlier, the Church had restated its commitment to keeping the meeting males-only, and requested that members of Ordain Women and the media stay away from the area.

Wearing pants to church was one of those wild, screeching ideas that barrels into an otherwise normal day. Stephanie Lauritzen was shopping at Target with her sister, who was not especially convinced that Mormon feminism was going to save the world. Lauritzen remembers her saying, “You guys are such a minority that you’ll never be able to grab the Church’s attention.”

To which Lauritzen, a mother of two, said: “No! There are a lot of Mormon feminists who are dissatisfied. The narrative that this is a group of weird little grumpy people is false.” She knew that Mormon feminists are a diverse bunch. Some of them wish Mormon women played bigger roles in Church administration. Some think Mormon families are too patriarchal. Some want women to be priests. So she challenged her sister, there in the aisles of Target, to pick some gesture, some symbol, that could test whether Mormon feminism was more than just a blogosphere of belligerent women.

“It has to be something I already do,” said her sister. “Like wearing pants to church.”

That was back in December 2012, not far from Salt Lake City. “Pants” has since become a proper noun in Lauritzen’s lexicon, meaning Pants Day 2012, a.k.a. “the Pantspocalpyse.” It was the day she gained a bit of faith in the strength and diversity of Mormon feminism, and lost a lot of faith in her church. A sizable group of women, probably more than a thousand across the U.S., wore pants to church instead of the customary Sunday clothes of a dress or skirt. They weren’t breaking any rules, and they weren’t staging a protest. They were basically trying on the slacks of feminist solidarity, for Sunday services anyway. Lauritzen and her co-organizers—who’d rallied around a blog post she’d written about civil disobedience—hoped to highlight gender inequality in Mormon culture, but past that, they left the event up for interpretation.

That was back in December 2012, not far from Salt Lake City. “Pants” has since become a proper noun in Lauritzen’s lexicon, meaning Pants Day 2012, a.k.a. “the Pantspocalpyse.” It was the day she gained a bit of faith in the strength and diversity of Mormon feminism, and lost a lot of faith in her church. A sizable group of women, probably more than a thousand across the U.S., wore pants to church instead of the customary Sunday clothes of a dress or skirt. They weren’t breaking any rules, and they weren’t staging a protest. They were basically trying on the slacks of feminist solidarity, for Sunday services anyway. Lauritzen and her co-organizers—who’d rallied around a blog post she’d written about civil disobedience—hoped to highlight gender inequality in Mormon culture, but past that, they left the event up for interpretation.

Wear Pants to Church Day turned a lot of heads. It ended up in the New York Times and NPR and Jezebel. A prominent Mormon feminist, Joanna Brooks, called it the “largest concerted Mormon feminist effort in history,” which is to say, much more than a group of weird little grumpy people. Many commentators wrote that it doesn’t matter what someone wears on the outside, as long as they’re ready to honor God on the inside.

On the other hand, even before the event took place, it was attacked by some Mormons as the disruption of a sacred space, or even the work of Satan. Lauritzen organized the event with an online group of Mormon feminists, but some of these critiques came directly to her inbox. On the Pants Day Facebook page, a few comments went so far as to seemingly threaten violence against women who dared participate.

“What the hell is WRONG with women in our society these days?” read one Facebook comment that was “liked” 75 times. “If you’re going to wear pants, they might as well get penis implants too, to make them even MORE masculine.”

Lauritzen was hoping Pants Day would show her why she loved her faith, but it brought out the best and worst of Mormonism. The negative response was far more vicious than she had feared. It was so harsh, in fact—so negative and intolerant, she felt—that despite the big success it represented for Mormon feminism, Pants Day was the day she started to give up on Mormonism.

“I was myself, as a member of the Church, not hiding who I was and not pretending to fit in or conform. And when I did that, I was basically universally rejected by my church.”

* * *

Pants Day 2012 was like a pair of stretchy jeans. It fit pretty well whether you were a longtime activist or a new feminist initiate, because it was flexible enough to mean different things. For some Mormons, it was the most unorthodox thing they’d do all year. For Hannah Wheelwright, an activist and student at Brigham Young University, it was a pretty typical Sunday in pants.

Pants Day 2012 was like a pair of stretchy jeans. It fit pretty well whether you were a longtime activist or a new feminist initiate, because it was flexible enough to mean different things. For some Mormons, it was the most unorthodox thing they’d do all year. For Hannah Wheelwright, an activist and student at Brigham Young University, it was a pretty typical Sunday in pants.

Wheelwright had started wearing pants while working for the Church, because she was wearing her Sunday best 7 days a week, and she didn’t like crossing her legs all the time. So when she heard of the event, it was only logical that she’d participate. “I like Pants Sunday,” she said, “because while it’s such a simple and innocuous act, it invites conversations that are difficult to achieve otherwise.”

The ripple of conversation reached Provo, Utah, on a Monday night in January 2013, a month after Stephanie Lauritzen had felt her faith start to erode. Wheelwright had invited a couple dozen young Mormons into a living room. She was wearing green eye shadow that matched her skinny jeans.

Wheelwright had some questions for the group: Is wearing pants to church a useful tactic? Could civil disobedience change Mormonism?

After a moment, hands started rising into the air, and didn’t really stop for the rest of the night.

“I think it was a big success. It brought feminism into the figurative room.”

“Yeah—it brought wordless conversations into the chapel, whereas it’s been in the blogosphere.”

The walls were baby-blue and decorated with Beatles posters. As attendees showed up they filled in a circle of chairs, which slowly expanded into the rectangular shape of the room.

“We have to remember that the Church has a persecution complex. When people question it, it tends to feel like it’s under attack.”

“We have to remember that the Church has a persecution complex. When people question it, it tends to feel like it’s under attack.”

“Well, you know you’ve succeeded when you start getting hate mail.”

For most Mormons, Monday night is full of games, prayer, or music in observance of Family Home Evening. This Monday was a little different. Wheelwright had thrown a feminist-themed party once, and a bunch of guys had asked her if she’d consider making it a regular thing. They liked talking about feminism, but they didn’t necessarily want to venture into the argumentative minefield of blogs and Facebook comments. So she’d founded Feminist Home Evening.

This was one of the places where Pants Day started to take on a life of its own, as it ricocheted through Mormon blog posts and living rooms. The group was around two-thirds women, mostly college-age. It included a man dressed in bright pink, and a woman with posture so perfectly upright that she resembled a church spire.

“At least you can run faster in pants,” said Wheelwright, as if Mormon feminists should be prepared to outrun a mob armed with torches and pitchforks. Then she posed one more question for the group: Should Mormon women be ordained into the priesthood?

Mormon priests are different than most kinds of Christian clergy: all young men in good standing become priests at 12 years old, and this empowers them to convert new members and take up men-only leadership positions. But Wheelwright knew her question was a contentious one. Polls suggest that only around 10% of Mormon women believe in female ordination, although for some reason, Mormon men are a good deal more supportive. So if Pants Day was a one-size-fits-all Mormon feminist event, female ordination was a custom-fit bra that only a select group would ever consider wearing.

Even so, at Feminist Home Evening, female ordination had some support. The most common Church argument—which does have a lot of traction among members—emphasizes that women already serve as mothers and as leaders in the women-only “Relief Society.” Women and men serve God in parallel, and shouldn’t have identical roles. But that view faced sharp critique in Provo.

“They don’t say the phrase exactly, but they’re talking about separate but equal,” said a young woman. Which is one reason, perhaps, to take up trousers, or go even further.

“We could write letters to all the stake presidents.”

“We could withhold our babies.”

“We could have a Slut Walk in Brigham Square.”

Feminist Home Evening walked a line between downright silly and dead serious. Pants Day was ultimately an intervention in Mormon culture: it questioned assumptions and attitudes, but it didn’t critique actual doctrine. Advocates of female ordination, including Hannah Wheelwright, are looking for change in the fundamental structure of Mormonism. And that’s liable to make some people upset, and perhaps require some comic relief along the way.

Debate continued late into the night, burning with an almost religious fervor.

* * *

The Internet has gotten good at turning words into action and back into words again. Back in December 2012, Stephanie Lauritzen posted her blog post about civil disobedience and accidentally invented Pants Day. Which took place around a week later, and appeared in newspaper articles and more blog posts, and trickled its way into the discussion at Feminist Home Evening. Which twirled around in the brain of Hannah Wheelwright, who helped spread the digital word on her Young Mormon Feminists blog and the website of a new organization called Ordain Women. Which then, in October 2013, proceeded to organize 150 women in front of the Salt Lake City Tabernacle.

The Internet has gotten good at turning words into action and back into words again. Back in December 2012, Stephanie Lauritzen posted her blog post about civil disobedience and accidentally invented Pants Day. Which took place around a week later, and appeared in newspaper articles and more blog posts, and trickled its way into the discussion at Feminist Home Evening. Which twirled around in the brain of Hannah Wheelwright, who helped spread the digital word on her Young Mormon Feminists blog and the website of a new organization called Ordain Women. Which then, in October 2013, proceeded to organize 150 women in front of the Salt Lake City Tabernacle.

They made a long line on a Saturday afternoon, asking for access to the males-only session inside. In effect, they were asking for the priesthood rights that all men receive. Husbands and male supporters stood to the side as one woman after another approached a Church representative, who smiled and calmly told them that entering the building wouldn’t be possible. Some of the women were crestfallen, though at least as many were unsurprised.

“I walked to the Tabernacle filled with hope, faith and (perhaps delusional) optimism,” wrote one of the event’s founders, Kate Kelly, on her blog. Ordain Women was a group that spanned 3 generations—from Hannah Wheelwright, 20 years old, to women who could have been her grandmother, who’d been fighting to ordain women since the 1980s. Kelly went on: “It felt like I was reaching out a hand of friendship and hope to someone who callously slapped that hand away, smiling all the while.”

This wasn’t a new feeling for many participants. The first wave of Mormon feminism—which pushed for almost all the same goals as today’s Mormon feminists—had hit a seawall of resistance from the Church. In 1993, several Mormon scholars were cast out of the Church for dissenting views, including feminist perspectives on Church history. The Ordain Women organizer Margaret Toscano was excommunicated in 2000. Feminism within the Church still hasn’t fully shed those associations, and that’s one reason that Ordain Women was a group of mixed belief. Though many in attendance were lifelong believers with a deep commitment to their church, some were doubtful or lapsed Mormons.

Stephanie Lauritzen had showed up, and she fit into the latter camp. She’d started to see her church as a sort of ex-boyfriend, who she still saw, but always with complicated feelings. She attended Ordain Women’s event partly out of responsibility. “Last year I asked Mormon Women to do something,” she wrote on her blog. “So when they answered my call, and supported me in wearing pants to church, I didn’t want to give up on them when they wanted me to stand in line for Priesthood.”

Unlike most ex-boyfriends, Lauritzen’s church happened to have a spokeswoman at the Ordain Women event. The spokeswoman described Ordain Women as divisive and unrepresentative of Mormon women as a whole. (Church spokespeople declined to be interviewed for this story). It was a familiar refrain in the ears of Mormon feminists, who have long pushed for recognition as a mainstream force in Mormonism, but it still pained Lauritzen to hear. She felt like the Church wasn’t giving them the space to present peaceful dissent. “I don’t need them to agree with me,” she said, “I just need them to see me as a person and not a threat.”

After the event, she found a photograph of herself on a feminist blog, a tear running down her cheek and a sad-looking smile on her face. It unsettled her because her sadness looked so accurate. “I’m embarrassed that I let my vulnerability show to people who don’t understand,” she wrote. “I’m embarrassed when it is passed around as an example of bravery or courage because mostly I feel like an imposter. I’m a person who has lost a lot in the last 10 months, who has given up orthodoxy and belief but is afraid of being a quitter.”

Lauritzen’s stopped writing on her blog for a long time after that. Wheelwright, Kelly, and the rest of Ordain Women wrote with a new intensity. At first, they wrote about the frustration and disappointment that had followed their first event. Then they started talking about the next one.

* * *

When December 2013 rolled around, Pants Day had lost its founder but gained, among other things, a self-described moderate Mormon feminist named Kristine Anderson. A team of organizers publicized the event on Facebook again, and talked to journalists again, and zipped up their pants and blogged and attracted critique again. Anderson heard about it and decided to take part.

When December 2013 rolled around, Pants Day had lost its founder but gained, among other things, a self-described moderate Mormon feminist named Kristine Anderson. A team of organizers publicized the event on Facebook again, and talked to journalists again, and zipped up their pants and blogged and attracted critique again. Anderson heard about it and decided to take part.

She explained her motivations on her blog, Confessions of a Moderate Mormon Feminist, emphasizing: No, I don’t think women should hold the priesthood. No, I don’t think that there are no innate differences between men and women. No, I’m not a liberal Mormon—I’ve never voted for a Democrat. And no, I don’t want to be a man.

“One of the reasons I decided to wear pants this year,” she said, “is because of the hostility I saw last year. You know—they should leave, they should be shot. I made a statement when I wore my pants to say that they are welcome here, they are our sisters, and they are accepted at the big table that Mormonism can be.”

But her two biggest reasons were simpler. Rexburg, Idaho, is a bitterly cold place. And sometimes, when she helps out with Primary, where Mormon children spend their Sundays, she crawls around playing with the kids.

Anderson isn’t your typical Mormon feminist. Not really because of her beliefs, though—rather, because there’s hardly such thing as a typical Mormon feminist. Mormon feminism has as many distinct pockets as a pair of cargo pants. Some of the fracturing simply results from decentralized, grassroots organizing. But some of it seems to come from the stigma attached to the f-word, too, particularly when the priesthood is involved.

“In my life, there’s so much hostility to the more radical Mormon feminism regarding priesthood that I very much try to separate myself,” Anderson went on. “Most of the people I associate with are conservative and traditional enough that any mention of women receiving the priesthood shuts down all discussion. And is considered grounds, in their opinion, for excommunication. In their perception, women shouldn’t be able to enter our temples, and they shouldn’t be able to have full participation because of those beliefs.”

So the words Mormon and feminist have become equally contested, each tugged and transformed by each person who uses them. Lauritzen had noticed this too, saying: “After Pants the first time, everyone was claiming their territory. Like—’We’re the type of Mormon feminists who believe in female ordination!’ ‘Well, we’re the type of Mormon feminists who believe that women don’t need ordination, and we believe that changes should be made this way.’ Everyone sort of carved out their own piece of the Mormon feminist pie.” The question is whether those dozens of different voices add up to a clamor or a chorus.

“Feminist” was a bad word when Anderson was young. She was raised in the sort of traditional, tight-knit Mormon community that might be skeptical of whether Mitt Romney is a good enough Mormon. When Anderson got married, she was eager and ready to become the best mother she could be. “I had been taught my whole life that genders have roles to play, and the highest calling of womanhood is to be a mother—that is your role in this life.”

Then she tried getting pregnant, and couldn’t. “We pursued foster care and adoption, and medical intervention,” she said. She felt inadequate, surrounded by young mothers who seemed like ideal Mormon women. After years of trying, she decided that she needed to shift some of her goals, and she went to college for accounting. Along the way, she started meeting more non-Mormons, and started discovering jobs in which women were valued purely for the skills they could bring to an organization. She wouldn’t have called herself a feminist, but her views were starting to change.

She and her husband had a daughter in the end, with the help of in vitro fertilization. But a decade of struggle had transformed her views on motherhood. “For me to be a woman of God,” she said, “has so little to do with what role I fill, and so much more to do with my character. And being valiant in my testimony. And much less about how many children I have.”

There’s a difference, she came to feel, between Mormon culture and the Gospel that’s supposed to underpin it. The core principles—the Church’s fundamental doctrines—are sound, in her mind. It was the culture that needed some work. She’d talk to friends and family about this, and found herself defending and explaining feminist ideas. She started to think that she should be more than a feminist sympathizer or supporter or ally.

“I saw that if I claimed the label moderate Mormon feminist, and then people get to know me—they’ll go, ‘Oh! That’s not what I thought Mormon feminists were.’” It would be easier to show someone who she was—show someone her feminism—than to defend someone else’s. She wanted to emphasize a different ideal woman than the stereotypical Mormon mother. She wanted women to take jobs, if they wanted—but then, on the other hand, to feel like at-home motherhood could be a feminist calling, too. So Anderson used the f-word on herself.

Almost immediately, without meaning to, she found herself talking to friends and family about Ordain Women. As soon as the group went public, it made such a stir that it monopolized the very term Mormon feminist. “Every single discussion I had about Mormon feminism from that point on was about Ordain Women,” she said. “And I was very frustrated, because I felt like I couldn’t spend time on the message that I had because it was just dominating the conversation.”

But then, that was feminism: a collection of voices, some louder than others, some marginalized, some incendiary. “Somehow,” said Anderson, “this disjointed, disorganized mass of advocacy is going to move together somewhere. Into the future, and you just find your place in it, where you want to be, and hold on tight.”

A few weeks before she took part in Pants Day, Anderson addressed a blog post to her 8-year-old daughter. It was about why modesty was important in a person’s clothing, but also why modesty didn’t mean fitting a stereotype. The post made her sound a bit like both critics and sympathizers of Pants Day 2012, who’d argued that it doesn’t matter what you wear, just what you believe. It made feminism sound less like an earthly freedom to dress or talk or live a certain way, and more like a freedom to worship.

“Don’t ever consider what another person will think about you while choosing what you are going to wear,” she wrote. “I want you to wear clothes that are comfortable, that fit well, that make you feel good about yourself and give you confidence, that match your personality and that you like, and are appropriate for the activity. So please, stand in front of the mirror and think about the opinions of the people who mean the most: yourself and God.”

Photographs courtesy of Ordain Women and Wear Pants to Church Day.

Daniel A. Gross is a freelance writer and public radio producer who currently lives in Berlin.