This post, and several others to appear in due course, are generously sponsored by a gentleman-scholar from County San Francisco, supportive of the production and assessment of nasty novels, dealing familiarly with gamblers, misandrists and flashy reprobates. Said gentleman-scholar has re-upped his donation, so keep pitching me, academics longing for freedom.

This post, and several others to appear in due course, are generously sponsored by a gentleman-scholar from County San Francisco, supportive of the production and assessment of nasty novels, dealing familiarly with gamblers, misandrists and flashy reprobates. Said gentleman-scholar has re-upped his donation, so keep pitching me, academics longing for freedom.

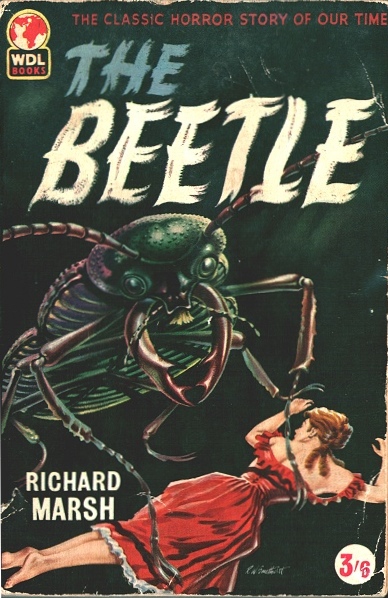

In the mid-1890s, two Victorian writers made a bet over which one of them could create a more frightening literary monster. The writers were Bram Stoker and Richard Marsh, and the books, both published in 1897, were Dracula and The Beetle.

Marsh won that bet by a landslide. TWIST.

A few addendums to this story: it’s probably not true. It’s the sort of story English lit students like to tell each other because of that twist ending I mentioned. I also like to tell that story, being an English lit student myself, and I enjoy spreading gossip about dead Victorian writers. It amuses me. But also! The Beetle. When Dracula was in its tenth printing in 1913, The Beetle was in its fifteenth. The Beetle even beat Dracula to film: the first (and ultimately only) Beetle film was released in 1919, while Dracula didn’t make it until 1922’s Nosferatu, which wasn’t even an authorized adaptation. Winner: Marsh.

But by the 1960s, The Beetle was no longer in print, and has largely been forgotten except by academics, who still love it. With such good reason, too. But first, a few words on late Victorian horror writing!

Gothic fiction had been around for over a hundred years by the 1890s, originating in works by Horace Walpole (The Castle of Otranto, 1764) and Ann Radcliffe (so many, 1789-1797). These works are filled with maniacal apparitions, giant helmets appearing out of nowhere, and crumbling castles in far-off lands like Italy and Not Bath. In the 19th century, the preoccupations of Gothic fiction changed a bit to include that devil, Science. But speaking generally, and with notable exceptions (see: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), Gothic fiction had trouble keeping up with the changing preoccupations and anxieties of Victorian writers and readers.

A lot had changed since Ann Radcliffe, to be sure. We’re talking about a world that, within the span of a couple of generations, experienced the Industrial Revolution, the discovery that the earth was more than 6,000 years old (it’s true!), the discovery of evolution (debatable. Just kidding, evolution is totally true), and the beginnings of imperial decline. Victorians of the late century perceived threats to conventional social morality everywhere, what with dandyism, ladies getting ideas, and even the loss of tight, toned n’ sexy men’s bodies that happens when men stop working the fields and live leisurely urban lives. English men and the women who loved them believed that the superiority they were convinced they possessed over all other peoples was horribly threatened by all these dangers, more frightening than anything Gothic fiction could offer. On their own, each of these ideas was frightening enough for your average white English reader to contemplate.

But consider, if you are willing, some of the intersections of these factors that the Victorian mind creates: for example, that intersection between evolution and the “Orientals” of the various outposts of the Empire, from North Africa across the Middle East and Asia (i.e. non-Christian brown people). I know, such people are difficult to imagine. So difficult, that the imaginations of English* artists and writers often ran away with them. “Orientals” had been written about by everyone from Lord Byron to Edgar Allan Poe, and they were usually characterized in the same way: deeply passionate, uncivilized, warmongering, decadent and dissolute, unlike us civilized Victorians, am I right? Well, Edward Said explains Orientalism better than I can. But the fact is that English intellectuals were genuinely terrified of degeneration: literally, the theory that English civilization was in the process of being eroded by, and would eventually give way to, people of lesser biological, moral, and social stock. I recommend reading Max Nordau’s Degeneration, which even Freud thought was kind of farfetched.

So Gothic writing couldn’t really compete with the uncertainty and terror of real life. That is, until the late 1880s, when the genre resurfaced, amazingly. The long 1890s saw the publication of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine and The Island of Doctor Moreau (and also When the Sleeper Wakes, The Invisible Man, etc. etc.), and Arthur Machen’s supremely fucked up The Great God Pan, all of which deal with degeneration theory in largely similar fashion: society is in decline because of foreigners, scientists, homosexuality, Satan, &c.

Late Victorian Gothic is much less things-that-go-bump-in-the-night-y than 18th-century Gothic, more raped-by-monsters-and-burned-alive-y. If you like your sexuality horrific, your identities multiple, your boundaries between science and supernatural penetrable, and your humanity contaminated both physically and morally—all of this strictly in the sense of your reading preferences, of course—then fin de siècle Victorian Gothic fiction is absolutely the genre for you.**

Enter The Beetle!

The Beetle, more than almost any of these other titles, externalizes the threat to English morality squarely within the corrupting allure of mysterious Oriental power. The novel is told by four different narrators, which together form a cohesive narrative, but the jist is this: in his younger and more vulnerable years, an English fellow named Paul Lessingham took a trip to Egypt, ostensibly as a career move, but more accurately, in a thinly veiled attempt to enjoy wild sex with already-debauched foreign women (a common pursuit at the time). He was seduced by a beautiful woman and taken prisoner into an orgiastic, virgin-sacrificing cult that worships Isis. The Beetle, the cult’s leader, alternates between insect and human form, and appears neither male nor female (referred to alternately by different characters, but generally in scholarship as female). Paul escapes the cult after a long period of sexual torture by attempting to kill the Beetle, but he doesn’t quite finish the job. In the years since, Lessingham has become a dashing politician, and the Beetle has made her way to London so that she can take revenge.

The different books of the novel are narrated by various victims and witnesses to the Beetle’s crusade of vengeance: Robert Holt is the first narrator, a hapless derelict who stumbles across the Beetle in an abandoned house and becomes her slave. Book II belongs to Sydney Atherton, a dandy scientist who is happily at work inventing germ warfare (seriously) and is driven wild with jealousy over his childhood friend’s engagement to Lessingham. Atherton is also the only person who can master the Beetle: a cheap display of electric powers brings her to her knees, alternately begging and praying. Book III is narrated by Atherton’s childhood friend, Marjorie Linden, a thoughtful and progressive politician’s daughter who also becomes the Beetle’s slave. The final narrator is Augustus Champnell, “confidential agent,” the sort of fellow who Gets Things Done, who is hired by Lessingham and Atherton after the Beetle disappears with Marjorie. After the Beetle kidnaps Marjorie, and nearly all the characters (except for Atherton and Champnell) have been raped, some to the point of insanity and/or death, Champnell, Lessingham, and Atherton embark on a surprisingly unexciting train chase, whereupon the train crashes, the Beetle is killed (OR IS SHE), Holt dies, and, after several years of treatment for insanity, Marjorie is happily joined to Lessingham in holy matrimony.

We never see Lessingham or the Beetle’s point of view, because their views are irrelevant: the point of the novel is to thrill the reader by bearing witness to the evils of the Beetle with fresh eyes, over and over. The Beetle is the most nefarious sort of threat to the foundation of English civilization: in human form, she is hideously ugly, of indeterminate gender, and observed over and over to be horribly foreign. Holt and Atherton obsess over her foreignness, Lessingham is attracted to and repulsed by it, and even strangers on the street remark on it, recognizing the Beetle as an “Arab” because of her giant turban and ugly face. (!) She physically and mentally rapes both men and women of all classes, in the least coded language you can imagine a Victorian novel having—lots of “mounting” and “penetrating.” Without the Beetle’s presence, the novel is so very English: it’s practically a comedy of love triangles. She is the degraded, dissolute, dehumanized Oriental, who thinks only of sex and power: the independently minded Marjorie Linden and Dora Grayling might well devolve, without the tempering effect of masculine civility and scientific know-how.

It’s all deeply racist (if you haven’t discerned that already), alongside other popular novels like John Benjamin Burkes’ The Lustful Turk. Perhaps no more racist than anyone else writing at that time—certainly no less than Dracula—but The Beetle is forgotten because it can’t be essentialized and stripped of its Orientalist elements the way Dracula has been. It’s not a role for Robert Pattinson.

But academics love it, as I mentioned, for these same elements: its shameless Orientalism, representations of English superiority, and out-of-control popularity encapsulate so many English anxieties at the end of the 19th century. If you close your eyes, you can hear a thousand Masters’ dissertations gently coagulating in the distance. Which leaves us with one final question: who would win in a fight between the Beetle and Dracula. Or one hundred two-foot tall Draculas versus one ten-foot Beetle? Or one hundred two-foot tall Beetles against one ten-foot Dracula. The battle rages on.

*and French, which is something of a, but not entirely other, story.

** The other book for you is Kelly Hurley’s The Gothic Body, in which she outlines these tropes.

Margot Blankier is writing a doctoral thesis on Cinderella. It's going okay.