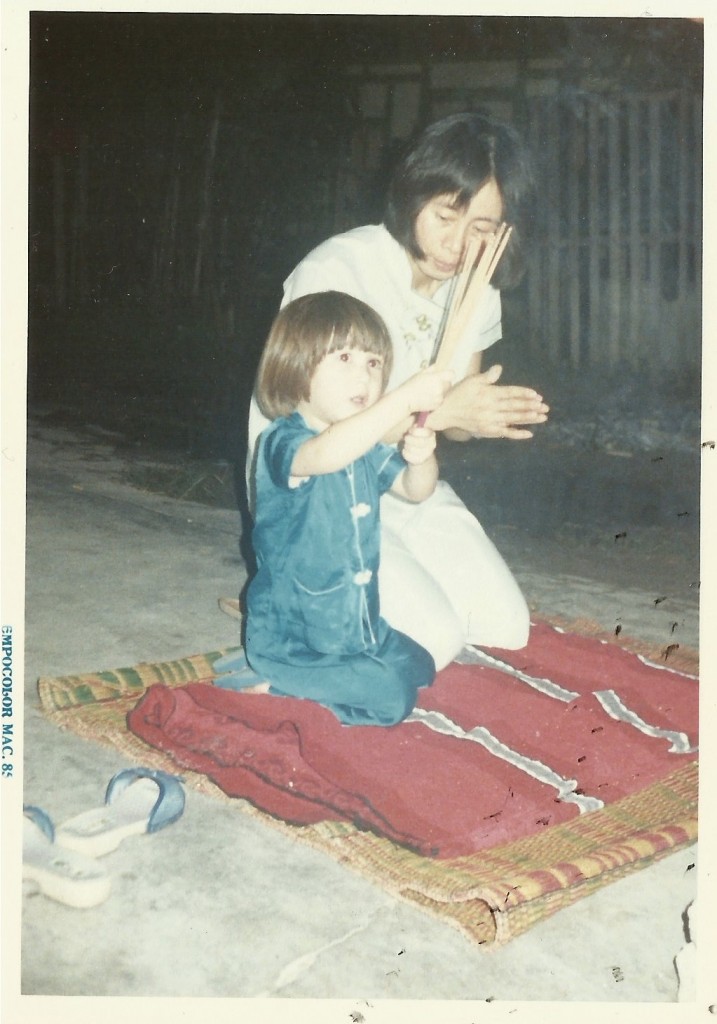

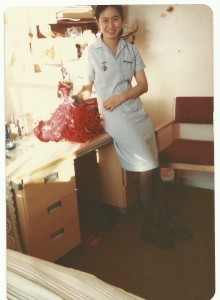

My third-generation Hokkien Chinese-Malaysian mum was born in Malaya, three years before its independence from Britain. Having the onerous position of being the third-born child and oldest girl in a family of twelve siblings, she grew up waking at 4am every day, going to the yard, killing a chicken and preparing it for her brothers and sisters. Later, having failed her Malay O-level and thus barred from nursing training in Malaysia, her Commonwealth status allowed her to get her qualification in Britain. She packed her bags, prayed to her ancestors the night before she left that she wouldn’t “fall in love with a white man,” and prepared to spend the next few years studying nursing in South London, before returning with her degree to work in Malaysia.

My third-generation Hokkien Chinese-Malaysian mum was born in Malaya, three years before its independence from Britain. Having the onerous position of being the third-born child and oldest girl in a family of twelve siblings, she grew up waking at 4am every day, going to the yard, killing a chicken and preparing it for her brothers and sisters. Later, having failed her Malay O-level and thus barred from nursing training in Malaysia, her Commonwealth status allowed her to get her qualification in Britain. She packed her bags, prayed to her ancestors the night before she left that she wouldn’t “fall in love with a white man,” and prepared to spend the next few years studying nursing in South London, before returning with her degree to work in Malaysia.

Apart from holidays, she wouldn’t return for over 30 years, having met my white British dad who was also studying to be a nurse. Of course, considering her prayers, this caused a great deal of grief in my family. After dating my dad for a while, my mum was told to end the relationship immediately. She did so, telling him that her family was more important but that they could remain “cycling and ping-pong friends.”

One day, whilst freewheeling down a hill together, she lost control, fell off, and landed directly on her chin. My dad said that when he picked her up he could see that her jaw had disappeared up into the rest of her face. She had it wired shut for three months, but my dad made her soup and milkshakes every day.

One day, whilst freewheeling down a hill together, she lost control, fell off, and landed directly on her chin. My dad said that when he picked her up he could see that her jaw had disappeared up into the rest of her face. She had it wired shut for three months, but my dad made her soup and milkshakes every day.

Hearing that this white guy seemed okay, my granddad gave them permission to marry, but informed my mum that if they ever got divorced, the family would disown her. They both retired from the NHS a couple of years ago and live in Malaysia now, where my dad is part of the family and my mum is finally warm and can stop bloody complaining about the bloody cold.

It wasn’t until I saw my mum trying to chat to a Malay person when I was seven that I realised she couldn’t speak the language all that well. It seems odd, to people living in Western countries with ethnic minority groups, that a third-generation descendant of immigrants wouldn’t be fluent in the main language of the country. Growing up in the Chinese area of Butterworth, near the island of Penang, she only knew other Chinese-Malaysians, and society was a bit of a Hokkien bubble. There was pressure, though, to learn either Malay or English. When the British left Malaysia in 1957, they helped write the new constitution, which stated that citizens had to be fluent in either English or Malay, instantly cutting off much of the huge Chinese population from their rights.

Mum got an A in English, making her choice, and off to London she flew, her education there instantly stymied by not being able to understand a word her Scottish teacher said.

A note on the names of my Aunties and Uncles: I call them numbered names in Chinese. I have Big Uncle, Uncles 2-5, Little Uncle and Uncle With No Number (he is my mum’s brother, but he was adopted away by my granddad at birth to my granddad’s brother, who had no sons, because of course that’s a tragedy that must be remedied by giving away your own), plus Aunties 2-4 and Little Auntie. My mum gets called Big Auntie by my cousins.

A note on the names of my Aunties and Uncles: I call them numbered names in Chinese. I have Big Uncle, Uncles 2-5, Little Uncle and Uncle With No Number (he is my mum’s brother, but he was adopted away by my granddad at birth to my granddad’s brother, who had no sons, because of course that’s a tragedy that must be remedied by giving away your own), plus Aunties 2-4 and Little Auntie. My mum gets called Big Auntie by my cousins.

Sometimes, visits to Malaysia resembled scenes from some kind of mad Chinese soap opera. At some point in the mid-90s, it transpired that Third Auntie was being beaten by her husband. The family convinced her to leave him and my mum flew us all back home to sort things out. Third Auntie, my mum and Second Uncle went round her house to pack her stuff. Second Uncle was also born into the British Empire, later joining the Malaysian Communist Party and the Communist Insurgency War, which started in 1967. At this stage of his life he was a hardcore Buddhist, though he was allowed back into the country from exile in Thailand once a year. Third Auntie’s husband was at home when they arrived and realised immediately what they were up to.

He punched my former-guerilla-lieutenant uncle in the face and knocked him out cold, then grabbed a machete, cut off his ring finger, threw his finger at my mum and ran out the house. My mum, nursing skills taking over, put the finger in the freezer in case he wanted it back.

Third Auntie eventually went back to him, as Malaysian law decreed that the nine-fingered man would get the children in the divorce.

This visit was only about the second time I’d ever met Second Uncle, living in Thailand as he did. My family didn’t see him once during the nine years he lived in the jungle with the MCP. My mum told me of seeing military helicopters flying overhead, off to fight her brother while she was in the school playground, and that one time he supposedly survived by eating a tiger. The mostly-Chinese MCP was illegal under British rule, but during WW2 were the main Malaysian resistance force against the Japanese, after the Brits scarpered (for a great novel that includes action involving the MCP and a half-Chinese-Malaysian protagonist [we never get those!], see Tan Twan Eng’s The Gift of Rain).

Post-war, the British came back after the Japanese left, reclaiming what was never theirs in the first place. The MCP continued to push for independence from Britain and began some serious guerilla warfare known as the Malayan Emergency. My uncle joined a second attempt to oust the government, fighting throughout the 1970s with his wife. They now live happily in Thailand with their daughters.

My grandparents weren’t wealthy but in 1952, two years before my mum was born, my granddad won the lottery. He used the money to buy businesses – rubber plantations and textile factories mostly, as well as a lot of land in their village, which finally got electricity when my mum was 15, in 1969. Their house got the first TV in 1970, having everyone in town over to watch the World Cup. During my mum’s teenage years, though, he lost everything except for one factory because of “bad friends,” I am told. He and his sons slowly built their empire back up again.

On my first day of secondary school, I met Michelle. Our classmates laughed, saying we looked like identical twins. Her mum was Chinese-Malaysian, her parents both worked in the NHS and her granddad also came into a large sum of money only to lose it all again a few years later.

A few years ago, I met Leo, whose dad is Chinese-Malaysian from Penang. We swapped notes and his granddad had also won the lottery, bought businesses and then lost it all again a few years later. It isn’t a conversation that you expect to have three times in your life. I’ve met more half-Chinese-Malaysian people whose granddads won the lottery than those whose didn’t. I just wonder: are there any other half-Chinese-Malaysian descendants of lottery winners/losers out there? Get in touch. What did your granddads do with their money and did any of them manage to hang on to it?

A lot of economic power in Malaysia has been concentrated in the Chinese population (and of course the British). When the British left, they helped draft the controversial Article 153 of the Constitution, which gives “privileges” to the Malay population, ostensibly to help redress some of this economic imbalance. It says that business and educational interests of the bumiputra will be safeguarded. There has been so much debate about the Article, what it has achieved and whether it should now be scrapped.

Apart from retelling these stories, fiercely supporting the Malaysian Men’s Doubles Badminton team, and feeling obliged to “be more Chinese” because of guilt-tripping by my mum, I don’t know what I have to contribute to the whole mess. Growing up in my own bubble – a liberal, socialist British one – it’s difficult to judge what happens in Malaysia now (specifically when my family members do or say something eye-poppingly racist) without knowing everything the British did to meddle in that country’s affairs. I wish my auntie hadn’t told me she had to wait with me at a coach stop because it was a Malay area. I wish my mum hadn’t been told by a smiling estate agent last year that she couldn’t buy a flat in a new condo building because they were reserved for the bumiputra. My family is privileged because of their economic status. They aren’t, because of their political one. The legacies of the Empire are many.